why young Sahrawis are joining military movement against Morocco

TINDOUF, Algeria — Since Moroccan authorities expelled United Nations personnel in March, a 25-year cease-fire has grown tenuous and the Sahrawi people seem to have lost hope for a peaceful resolution to their quest for independence.

The Sahrawi liberation movement, the Polisario Front, is attracting recruits — especially younger ones.

Walad Bujama, 21, joined the Polisario Front in 2015. His father lost his eye during the guerrilla war that the Sahrawi people unleashed against Morocco in 1975. His uncle died fighting the Moroccan invasion of Western Sahara in 1985. Despite the current danger, Bujama said, the long wait for a solution that could determine his future has made him ready to take up arms.

“I no longer believe the UN can reach a solution. I see war as the only remaining option,” he told Al-Monitor.

Bujama is a soldier of the front’s 7th Military Sector, based in the tiny town of Aghwinit. Polisario units are spread throughout the rocky hills that stand steady in the vast Sahara Desert. The region has been under Polisario’s control since the cease-fire.

Bujama’s division patrols the area surrounding Aghwinit on the border with Mauritania. It takes him five days to get to the refugee camp where his parents and two sisters live. Their house is made out of mud bricks.

Walad Bujama, a soldier of the Polisario Front's 7th Military Sector, directs a machine gun in Aghwinit, Western Sahara, April 23. (photo by Ramsak Rok)

Many Sahrawi youth have lost hope for a peaceful solution, he said, adding, “Most of my friends have joined the military recently."

A portable building near the base is used as a hospital to treat people who live in the Aghwinit area. Omar Albachir sits under the shadow of its walls to avoid the blazing sun. Albachir is a representative for young soldiers at the Sahrawi Youth Union, UJSARIO. His mission is to relay the concerns of young people in the military to the Polisario leadership to consider when making decisions.

He conducts monthly tours to listen to young people’s perspectives. “I believe that what has been taken by force can only be restored by force,” Albachir told Al-Monitor.

According to Albachir, young people represent 70% of the Sahrawi population in the camps. He was among the young people who met UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon during his March visit to the camps.

“The Sahrawi youth have reached the point that they are all prepared to be martyrs,” he said. When asked why, he said the targeting of Sahrawi people cannot be “excused.” He gave as an example the February killing of a Sahrawi cameleer, which Ban cited in his recent annual report as a possible violation of the cease-fire by Moroccan soldiers.

Ban presented his report April 19 to the United Nations Security Council, recommending that UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara — known by its French acronym, MINURSO — be extended. It is due to expire at the end of April.

Ban presented his report April 19 to the United Nations Security Council, recommending that UN Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara — known by its French acronym, MINURSO — be extended. It is due to expire at the end of April.

Ban has repeatedly called for negotiations without preconditions between Morocco and the Polisario Front, but the UN focus has been more on restoring its mission in the region after its civil and political representatives were expelled when Ban visited the Sahrawi refugee camps March 5. The conflict has been in a stalemate, and there has been no indication of a solution yet.

During the last decade, there has been a major turning of events in the geopolitical map of North Africa as it became more susceptible to violence after the collapse of Libyan President Moammar Gadhafi’s rule in 2011. Western Sahara was no exception. The movement established the Gdeim Izik camp, among others, to demand socio-political rights and soon raised the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) flag calling for Independence. It took a month for Moroccan authorities to disperse the camps, which were estimated to hold 20,000 people at that time, according to media activist Hamdi Mayara, who helped build the camps.

Should violence erupt again, Albachir said the Sahrawi people have the right to respond to anyone who tries to interfere. “No one will be excepted if war takes place, including France and Spain,” he told Al-Monitor.

France has been a strong ally of Morocco in the Security Council and has been supporting the Moroccan monarchy’s proposal for Western Sahara’s autonomy rather than independence. Spain’s foreign minister recently suggested that the MINURSO mandate should be extended for two months. According to Albachir, no one can predict what will happen if the peace process ends, as there will be many mercenary groups waiting to work for the highest bidder.

“Recently, Libya has seen the creation of many such entities that have been forming serious obstacles [to security],” he added.

The liberation movement isn’t just attracting young people — it’s attracting young, educated people. Sidahmed Jouly, who holds a master’s degree in politics from Hassiba Ben Bouali University in Chlef, Algeria, has chosen to enroll in a Polisario military preparatory school.

“I can only follow the path of those who have sacrificed their lives for us,” he told Al-Monitor.

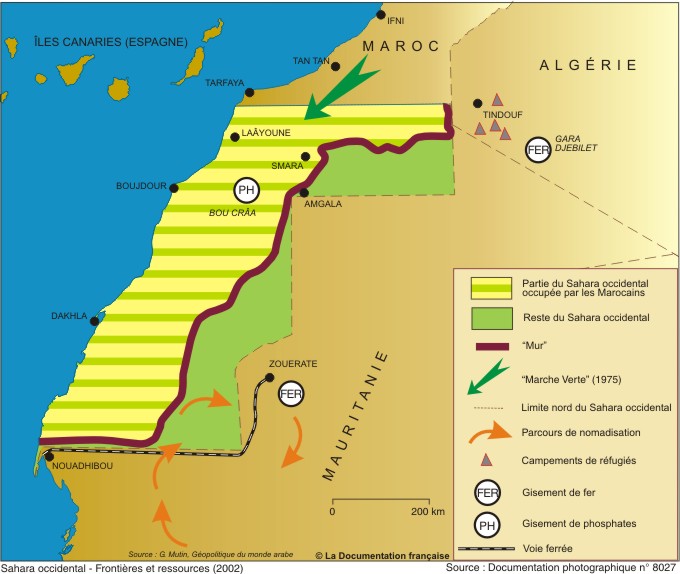

Thousands of Sahrawis have studied in Algeria, Cuba, Libya and European countries — mostly Spain. After a recent call on Sahrawi national radio, which airs in the refugee camps and the Moroccan-occupied territories of Western Sahara, many educated youth have decided to start their careers as soldiers after graduating and finding no job opportunities in the camps. Jobs are scarce despite the potential wealth of mineral-rich Western Sahara. Billions of dollars' worth of resources, especially in fish and phosphates, are controlled by Morocco.

In the meantime, most of the Sahrawi refugees who have created a state system in exile volunteer for their cause in the harsh conditions of the Hammada desert.

“We are supposed to reconquer our land by any means,” Jouly told Al-Monitor.

http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2016/04/sahrawi-youth-movement-morocco-polisario-soldiers.html?utm_source=Al-Monitor+Newsletter+[English]&utm_campaign=b9e0c792df-April_29_2016&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_28264b27a0-b9e0c792df-102460321

Sahrawis watch a mine explode during a demonstration organized by officials from the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in the Sahara Desert in southwestern Algeria, Feb. 28, 2011. (photo by REUTERS/Juan Medina)

Sahrawis watch a mine explode during a demonstration organized by officials from the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in the Sahara Desert in southwestern Algeria, Feb. 28, 2011. (photo by REUTERS/Juan Medina)