"What’s Gerrymandering, Anyway?", TNYT

“A suggestion on a subject that many non-Americans don’t even know is different about the U.S.: gerrymandering. I’m from Spain, where ‘electoral districts’ match other administrative divisions that are very difficult to change (cities, provinces, regions).” — Mariluz Ochoa de Olza, Spain “A suggestion on a subject that many non-Americans don’t even know is different about the U.S.: gerrymandering. I’m from Spain, where ‘electoral districts’ match other administrative divisions that are very difficult to change (cities, provinces, regions).” — Mariluz Ochoa de Olza, Spain |

|

| Hearing these and many other questions on this nettlesome topic, I’m starting to feel slightly queasy about the unpleasant nature of our electoral system. I will now attempt to explain gerrymandering, a phenomenon nobody likes, unless they happen to be in power at the right time. |

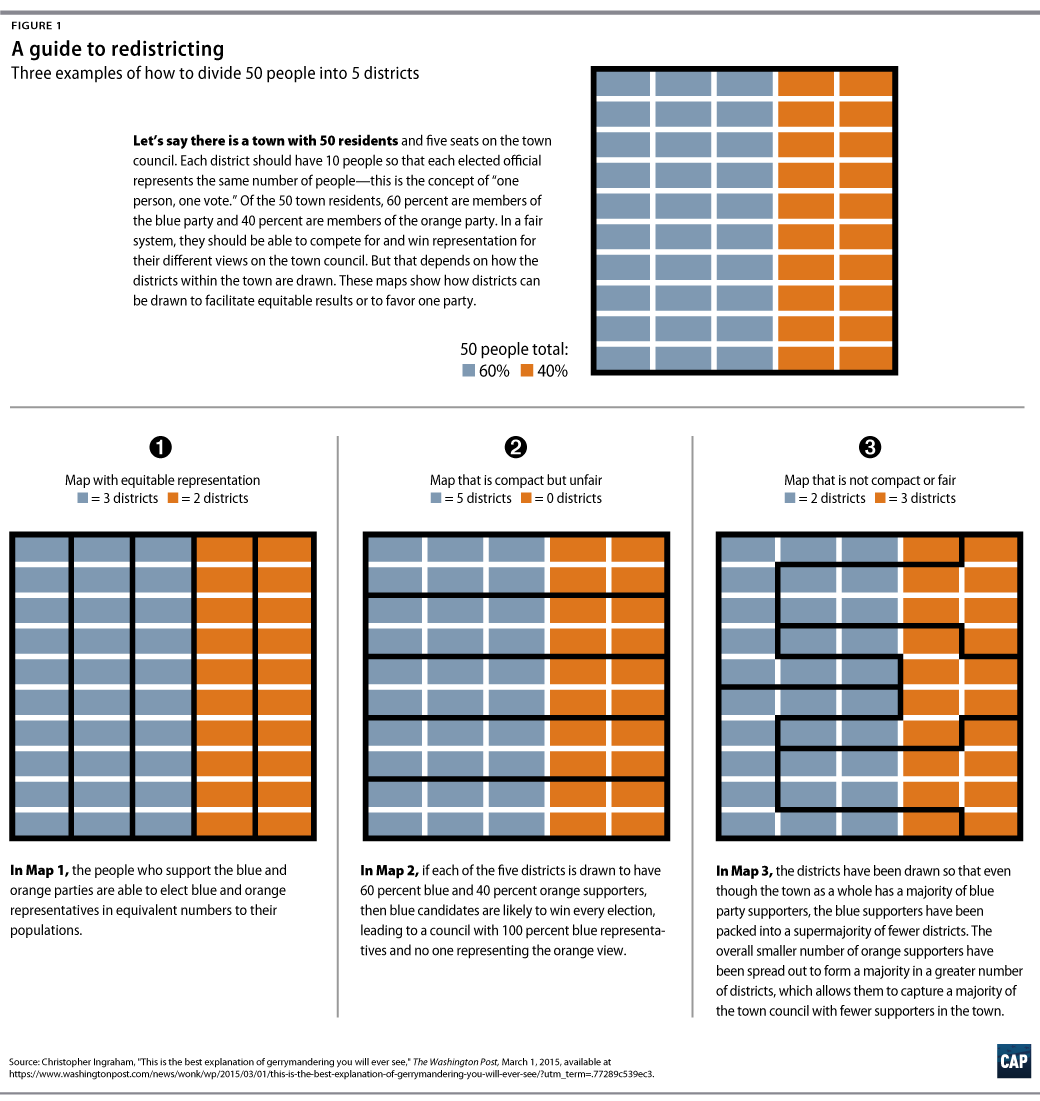

| Every 10 years, after the national census, the country’s states redraw the boundaries of their electoral districts. The new boundaries are generally drawn up by a state’s governor and Legislature, and so the party in power tries (without making it too obvious) to draw boundaries designed to benefit itself — a process known as gerrymandering. (With 50 different states, there are variations in how this works.) |

| The issue is important in 2018 because the next redistricting is in 2021, so governors and state legislators elected now to four-year terms will be in charge during the process. Last time around, in 2011, there were more Republicans than Democrats in control at the state level, and so today’s boundaries disproportionately benefit that party. |

| “If Democrats don’t win key elections this fall that allow them to have seats at the table in 2021, the party could face another decade in the wilderness,” David Daley, a redistricting expert, told Vox recently. |

| While the practice might be ugly, the term is elegant. It dates back to 1812, when Gov. Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts’s blatantly partisan new districts included one that meandered outrageously around, resembling some sort of newt. Gerrymander is a portmanteau, made up of the governor’s name and the word “salamander.” |

17-X-18